Constitutional Kaleidoscope on Religious Freedom

The Supreme Court is far from being as united on the issue of religious freedom as their unanimous ruling today would suggest.

The good news, if you will, out of Washington today is that with the unanimous decision of the Supreme Court, a Christian group may no longer be excluded from occasionally flying its banner on a municipal flagpole outside Boston’s city hall. The Nine put paid to a long campaign against the group by Boston, which had sought to shield what it deemed to be its purely secular domain from any expression of religion.

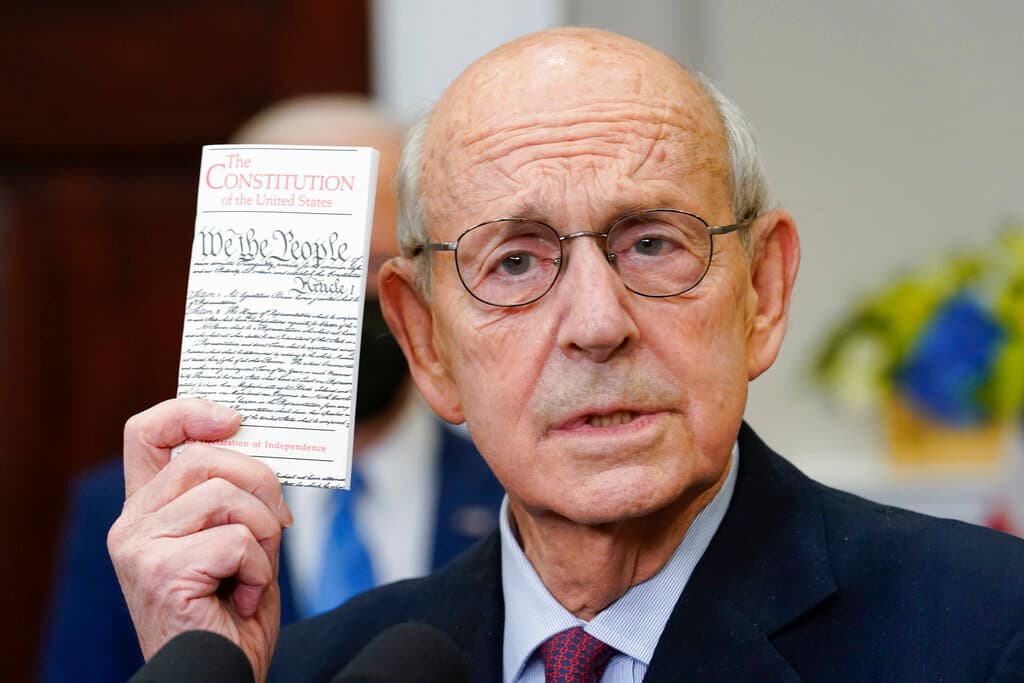

The bad news, if you will, is that the mildness of the opinion, drafted by Justice Stephen Breyer, seems to have inspired the court’s conservatives to chime in with three concurrences, each emphasizing different aspects of jurisprudence on the question of religious freedom. This constitutional kaleidoscope suggests that our high court is far from being as united on the issues as their unanimous ruling would suggest.

The case centered on a group called Camp Constitution, the mission of which is to “enhance understanding of our Judeo-Christian moral heritage,” not to mention “the genius” of the Constitution. The group contended it was blocked from the honor of flying its symbol, which featured a Christian cross, on the aforementioned flagpole, even as numerous other organizations got permission from Boston to fly their own standards.

Justice Breyer’s opinion centers on the point that when “government encourages diverse expression,” or creates “a forum for debate” it cannot, under the First Amendment, discriminate “against speakers based on their viewpoint.” Yet if government “speaks for itself,” there is, Justice Breyer writes, no First Amendment requirement to provide “airtime for all views.” So Boston could “refuse flags based on viewpoint.”

After all, Justice Breyer observes, “Boston could not easily congratulate the Red Sox on a victory were the city powerless to decline to simultaneously transmit the views of disappointed Yankees fans.” Under the Constitution, Justice Breyer adds, it is “the ballot box,” and not “rules against viewpoint discrimination” that serves “to check the government when it speaks.” Yet, he reasons, Boston’s city flagpoles are a forum.

That finding contrasts with Boston’s view that the banners it permitted to wave on the municipal flagpole “reflect particular city-approved values or views.” While Justice Breyer observed that “may well be true of the Pride Flag raised annually to commemorate Boston Pride Week,” he found it “more difficult to discern a connection to the city” when a local bank, the Metro Credit Union, also held a flag raising at city hall.

Justice Breyer’s evenhandedness is reminiscent of his concurrence in a 2005 case over the display of the Ten Commandments at Texas’ state capitol, where he said the First Amendment “does not compel the government to purge from the public sphere all that in any way partakes of the religious.” He endorsed a “relation between government and religion” as “one of separation, but not of mutual hostility and suspicion.”

It was hardly the full-throated battle-cry of a religious freedom crusader. Yet compare Justice Breyer’s reasoned concurrence in that Texas case with Justice David Souter’s dissent, on grounds that “any citizen should be able to visit” the state capitol “without having to confront religious expressions.” Justice Souter’s secularist sensibilities were offended merely by Texas “putting the Commandments there to be seen.”

In the Boston opinion, Justice Breyer’s equanimity over the cause of religious freedom is plain. Boston’s “lack of meaningful involvement in the selection of flags” or their messages “leads us to classify the flag raisings as private, not government, speech,” he wrote, yet “nothing prevents Boston from changing its policies going forward.” How is that not an invitation to defy the court’s ruling?

That aspect of Justice Breyer’s ruling was swamped with a chorus of concurrences. Justice Samuel Alito disagreed with any need “to consider history, public perception, or control in the abstract” when weighing whether speech was by the government or a private party. Justice Brett Kavanaugh stressed that governments “may not treat religious persons, religious organizations, or religious speech as second-class.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch aimed at the Lemon test, devised by the court to weigh religious expression questions. Boston had cited it to block the flag. Justice Gorsuch called the test “an anomaly and mistake.” We’d like to think that the unanimous court might get a bit more Moxie in respect of religious freedom with the accession of Justice Breyer’s successor, Ketanji Brown Jackson. She began her acceptance of President Biden’s nomination by “thanking God for delivering me to this point.” Amen, we say.